Another assignment in my Abnormal Psychology class was to relate three ideas between this TED Talk and the class’s textbook (Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach by D. H. Barlow and V. M. Durand). Here it is.

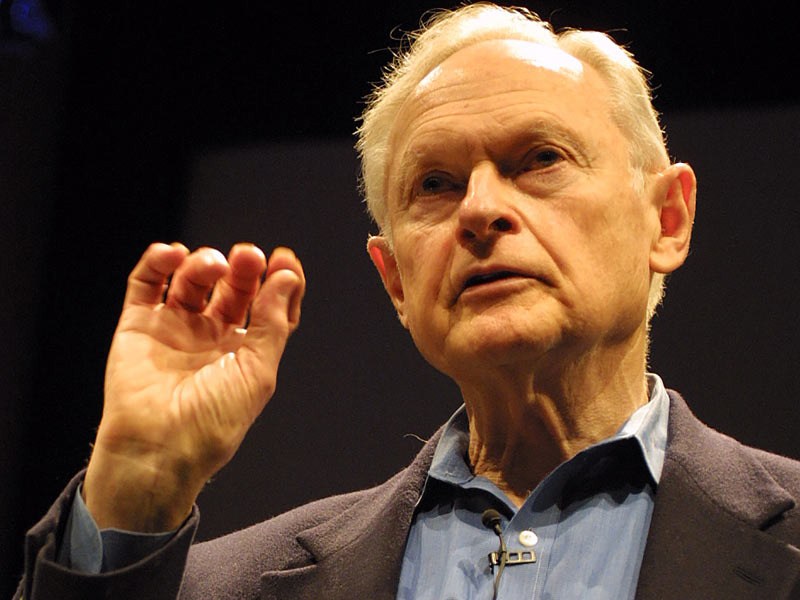

Gender identity is a very fundamental aspect of an individual’s personality that colors nearly every social interaction and experience in their life. Gender itself is a social construct that mostly influences other people’s interactions with an individual. Gender dysphoria is when an individual’s physical/biological sex, termed their “natal sex,” matches their assigned gender but not their gender identity—these individuals are transgender. Because natal sex and gender are so often and incorrectly used synonymously, the TEDx Talk by Rikki Arundel explained the difference, as well as other issues presented with being transgender (or transsexual, as the book calls it). Some of these issues include the distinction between gender and sexual arousal patterns, gender nonconformity for men and women, and the effects of gender nonconformity in children.

One of the first items addressed in the video was the difference between gender and sexual arousal patterns (or sexual orientation). Since the concepts of gender, natal sex, and sexuality are so closely connected, it unsurprisingly confuses some people, as evidenced by Arundel’s anecdotes. There are indeed similarities between an individual behaving in ways that are more consistent with the opposite gender for sexual gratification, and doing the same to alleviate gender dysphoria. However, the former is a form of paraphilic disorder called transvestic fetishism, and the latter is no longer considered a mental illness by the mental health community. Also, a transgender individual identifying as a man, for example, would not necessarily identify as being attracted to women, the conventional sexual orientation for that gender. Sexual arousal patterns are considered independent to gender identity, and the desire of most transgender individuals is merely being able to live as the gender they feel they really are.

The book relates that there are three times as many men as women who reject their natal sex, and the video says that individuals uncomfortable with their gender assigned at birth are 80% male to female. However, this is not because gender dysphoria affects men more than it does women. It is likely because gender nonconformity is generally easier for women than for men. Women have more leeway behaving and expressing themselves in gender-nonconforming ways, such as wearing men’s clothes and young girls playing with stereotypically boys’ toys. Both men and women undergo intense social pressures to conform, but men and boys assume more risk of being cast out for expressing interest in or taking on roles traditionally reserved for women, such as something as innocuous as liking the color pink.

Children are known to develop a concrete gender identity by the age of three. Whether gender identity is innate or a result of social factors is still being researched. What we do know is, as soon as children are born and their sex is assessed, they are subjected to social pressures to fit into the gender mold they are given. Most children’s toy sections in stores capitalize on this and create a divisive line across which most kids do not dare to cross. Both boys and girls are bullied or at least encouraged by their peers and families to conform to their assigned gender, and boys especially are forced to defeminize to avoid being ostracized.

Distinguishing between gender and sexual orientation, the inherent social differences between men and women, and the influence of gender on children are not the most popular talking points with regard to transgender issues in the media. Arundel’s personal experience and study of this topic gave incredible insight into these areas. The book is also very helpful in describing the research and statistics surrounding these topics, but it does use the term “transsexual.” This seems to me that it would generate more difficulty in distinguishing between gender identity and sexual arousal patterns, since it is so similar to terms like “homosexual,” “heterosexual,” and “bisexual.” I think the book should start using the term “transgender,” which is more widely accepted today as a descriptor for people with gender dysphoria.